The Corporate Merger of Political Design

The design of the Harris campaign reflects how western politics has been captured by corporate culture. And here we are.

There's a big election on Tuesday and no-one's excited about it. In fact the anxiety in the air is palpable, the polls on a knife edge. The only people who seem genuinely excited about winning are deluded real estate agents and/or rabid fascists, while everyone else simply hopes for the least worst thing to happen.

As someone who pays attention to design and branding, I'm interested in how this story of politics is reflected in the way campaigns and parties present themselves. I think the evolution of political branding helps tell the story of the corporate capture of political culture, and the plummeting trust in western democratic systems.

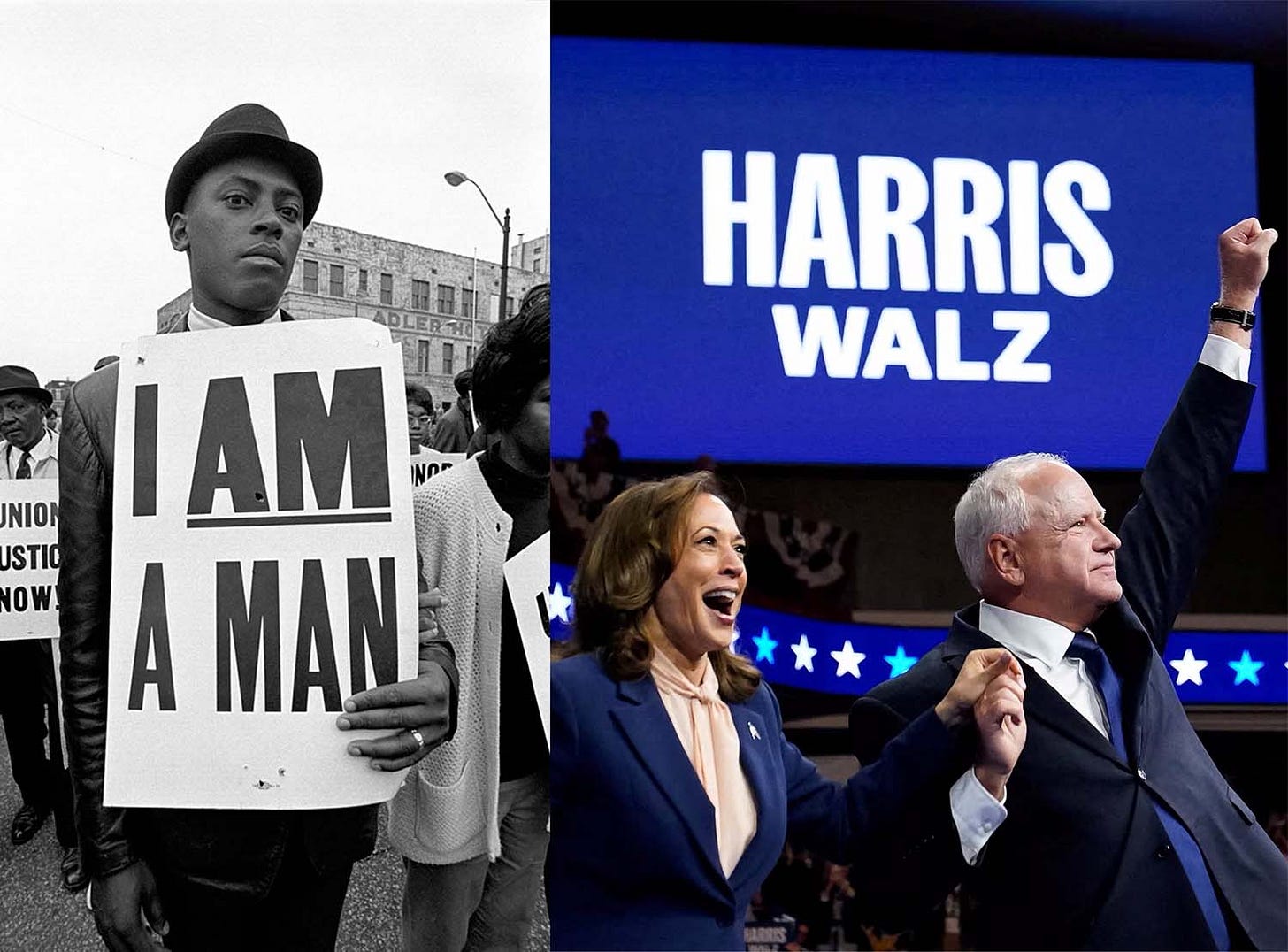

Kamala’s campaign design is a masterpiece of minimal nuance. Subtly cribbing from civil rights era typography, eschewing any decorative stars, stripes or containers and dialling up the Democrat Blue to a refreshing shade that Yves Klein would approve of (and that brand designers are now all-too-familiar with) to convey a refreshing sense of directness and authenticity all within a simple yard sign. Yet it's so well balanced and considered that it betrays a cosmetic approach to politics, wrapped in the sleak sheen of a coastal startup.

The campaign is simply too good at branding.

For corporations, branding is crucial. It’s the difference between Coke and Pepsi, between a Whopper and a Big Mac. When you’re selling the exact same product, you have to manufacture difference in the consumer’s mind. You can see where I’m going with this.

Brand Britain

The late nineties was the height of neoliberalism—arguably the historical peak of western liberal hegemony—perfectly encapsulated in the rebranding of Labour as ‘New Labour’.

Here, the corporate capture of party politics was up-front and celebrated. The government of Private Finance Initiatives brought in a wave of brand-friendly corporate partnerships, transforming a historically working class, socialist-leaning party—the party of labour—into a pro-business, pro-finance, fully capitalist party. New Labour was a shining vision of a progressive corporate utopia, and it changed the face of political campaigning both in the UK and the US.

Traditionally, political campaigning is about promoting policy, rallying supporters (and demonising minorities) and making leaders seem as inspirational and likeable as possible, while undermining the opposition. The New Labour campaign of the nineties embraced corporate influence, and opened up politics to the advertising industry and to the techniques of branding. Of course, advertisers have long played an influential role in politics, but here they were able to apply their learnings from the illustrious evolution of consumerism through the 20th century and the post-world-war boom.

Conditioned by Thatcher and Reagan, the public had settled into it's role as consumers, finding our self esteem and identity through association to different brands that offer the exact same products in different packages. New Labour began to define it's own difference through brand-association. This was the era of "Cool Britannia," in which British startups and their charismatic CEOs came to prominence on a cultural wave of Brit Pop and Young British Artists. Tony Blair was able to present himself as a young go-getter in the same mould as Richard Branson or James Dyson, who could unlock our entrepreneurial spirit and be an ambassador for "Brand Britain." In doing so, New Labour was pitched as brand over a political party. A consumer choice, free from the historical baggage of ideology and class conflict.

The Obama campaign of 2008 represented something of an evolution of this approach, using the techniques of corporate branding to full effect and becoming the first campaign to have something like a corporate logo. The ideas of 'Hope' and 'Change' were pitched more like brand values than anything grounded in actual policy, the party coalescing around a progressive, optimistic lifestyle brand. But this was mere moments before the crash. Before the booming economy finally bust, and the cracks in the foundation of the corporate ideology were plain to see.

When Hillary Clinton tried to replicate Obama's approach in 2016, commissioning her own corporate logo and design system, well, we saw what happened.

You could describe Trump as a sort of "anti-brand" in the way that his staunchly brash, unashamedly gauche aesthetic flies directly in the face of frictionless, faceless, liberal technocracy. While the Dems shrouded themselves in a shiny wrapper of corporate competence, Trump was brazenly unvarnished.

Kamala's campaign is keenly on-trend in its aesthetic, mirroring the output of the buzziest brand agencies: a visual marketing approach that any software-as-a-service, lifestyle or fintech company would be happy with. But this election (and the last two) shows evidence of a backlash against such a corporatisation of politics.

The world of brands is a world of passive participation, in which decisions that define people and their communities are largely substituted by a choice of products and services. In which consumers 'vote with their dollars' and the idea of 'freedom' is synonymous with 'choice.' When the primary way that we see ourselves shaping our world is as consumers, democracy becomes a matter of brand preference. And when both parties in a two-party system are vying for the same corporate donations, the decision becomes more and more like choosing between a Whopper and a Big Mac.

“When the primary way that we see ourselves shaping our world is as consumers, democracy becomes a matter of brand preference.”

But when you've been eating nothing but McDonalds and Burger King, you start to crave fibre, texture, substance.

I'm not trying to say that the design and branding of the Harris campaign will lose her the election, but that the design and branding of the Harris campaign reflects the reasons she is not as likely to beat Trump as she should be. A painstakingly considered surface level veneer of progressivism, a manner of indecipherable management-speak that belies a lack of conviction, and an undercurrent of cynical hawkish geopolitics and military alliances that undercut her attempts at seeming principled. The intangibility of it all.

When New Labour rebranded in the Nineties, they were riding a wave of cultural and economic prosperity in the UK. Slick, shiny brands like Virgin were the heroes of the day. Now we’re experiencing a massive loss of faith in capitalism and the corporations that feel so disconnected with to the public. The fact that her design is on-point serves only to add another layer of gloss to the package. Harris only offers a vague idea of corporate confidence. She offers a considered brand and an absence of politics. Like Coke partnering with Pepsi, she's pursued endorsements from Cheney and Bush: a tacit acknowledgment that it's all just sugar water.

There's no corporate sheen to Trump's campaign. Beyond the bluster, the lies and the grifts, what Trump is offering this time round is real: real bigotry, real hatred, real oppression. Terrifyingly real, but real nonetheless.

ALSO READ:

Blanding and flattening

Just as ‘form follows function,’ style should serve substance. A piece about the choice fallacy in graphic design, and how everything kind of looks the same, even if it looks different.

A great follow for design in politics: